Local firms get most Federal contracts that go to small businesses. Consolidation will change that.

Category Management shifts contracts to national and regional businesses, putting pressure on local firms

It used to be that local small businesses—including Main Street shops and family firms—could grow through Federal contracting. Those days are numbered. Federal buyers are chasing efficiency through category management, and that comes at the expense of local businesses.

The White House’s budget office issued a directive on Consolidating Federal Procurement Activities earlier this month. In the memo, numbered M-25-31, the Office of Management and Budget ordered Federal agencies to centralize both their contracts and their procurement functions, with the ultimate goal of “eliminating waste and saving taxpayer dollars.” Drek Hawkins pointed out that M-25-31 omits any mention of its effect on small businesses. Data shows that the effect will be eliminating local small businesses from the industrial base.

The OMB’s memo focuses on two goals: (1) increasing—and, in some cases, mandating—the adoption of category management, and (2) transferring purchasing activities from individual agencies to the General Services Administration. I’m planning a post on the GSA transfer for the future. But I’ll focus here on what will happen with more use of category management.

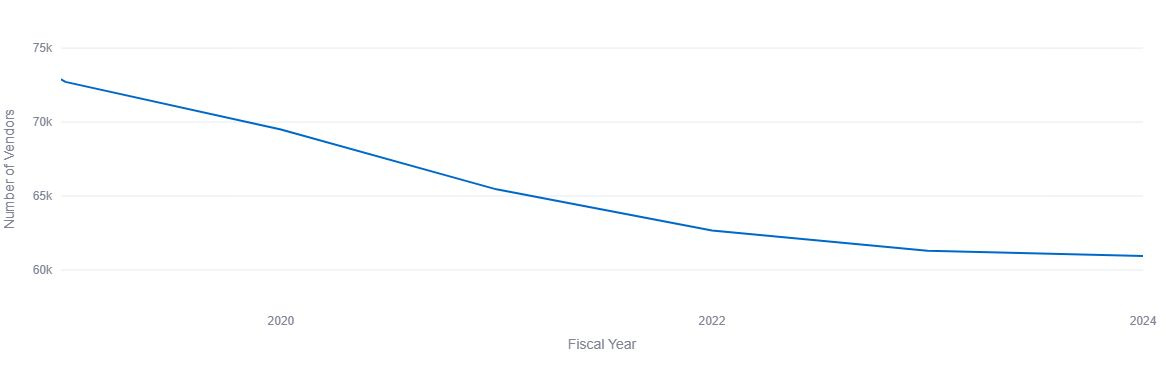

The decline in small-business participation

While in government, I served on the Federal government’s Category Management Leadership Council, and, to the Council’s credit, they took small-business considerations seriously. The category managers closely tracked their small-business spending and outreach. But spending is different from participation—the number of small businesses getting contracts.

Small-business participation in contracting has declined 16% since the White House formalized category management in 2019:

The federal government adopted category management from the private sector, where companies like IKEA pioneered the approach. The concept involves classifying spending into categories and then centralizing management of each category’s purchasing life-cycle, from forecasting to selecting suppliers. In the private sector, one of the explicit goals of category management is to reduce the number of suppliers. Consolidating suppliers gives the buyer more pricing leverage and, because there are fewer relationships to manage, lowers the overall cost of purchasing. IKEA reportedly went, in the period between the 1990s and 2010, from 2,500 suppliers to 1,074. So it should be no surprise that adopting category management shrunk the Federal government’s supplier base.

Category Management’s shift away from local

Who are these businesses being squeezed out of the government’s buying process? Data analysis shows that local small businesses are the ones hurt the most by category management.

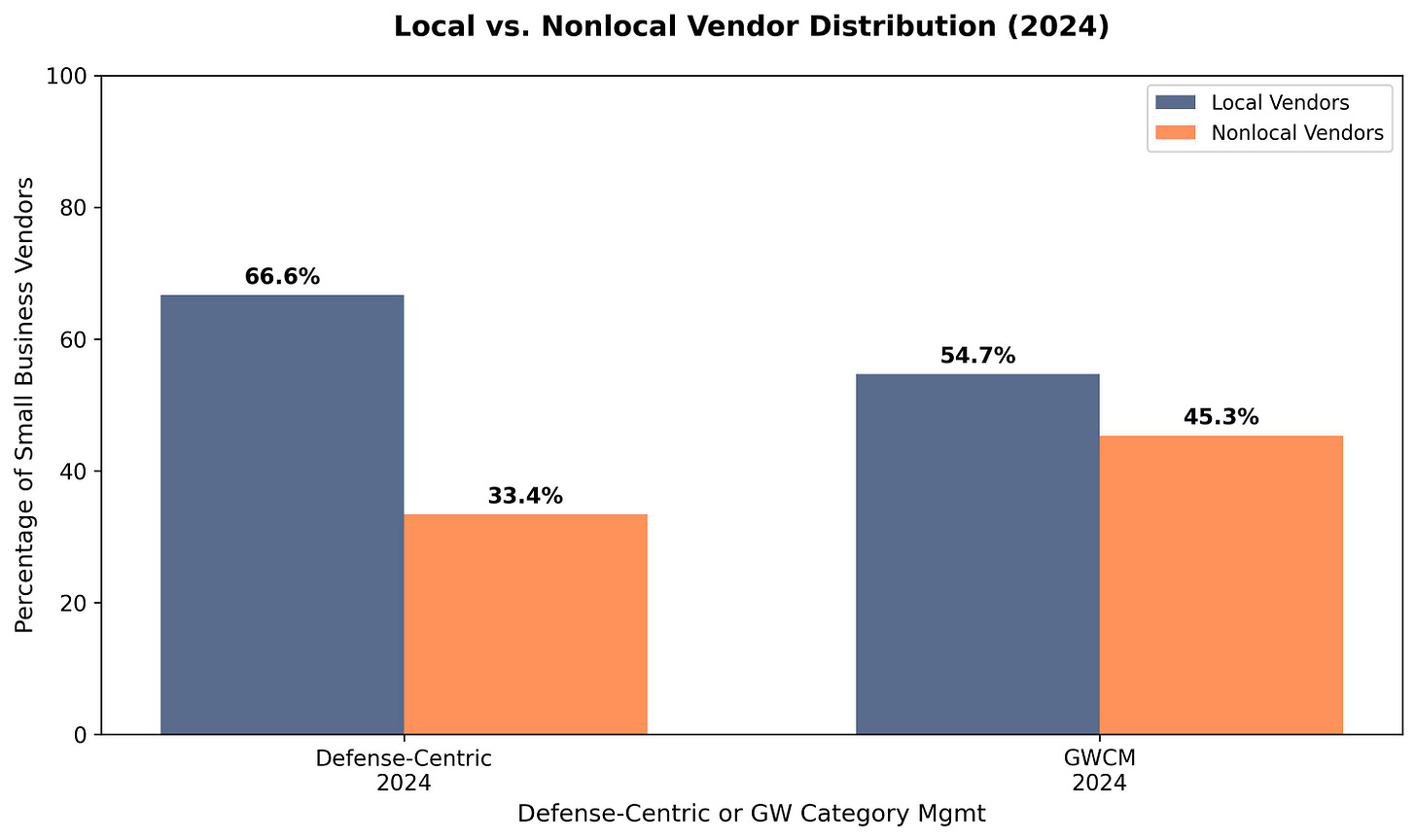

I defined “local” as a business that worked only on government projects within its own state. By comparing government contracts covered by the category-management process with those that aren’t, I found that local businesses fare much worse under category management. My analysis took advantage of a unique aspect of Federal category management. Not all government spending is covered by category management. Some industry sectors—designated as “defense-centric” because they are primarily used by the Department of Defense—are excluded from the OMB’s government-wide category management program, or GWCM.

Local small businesses are a much bigger part of the purchasing outside of category management. Local small businesses make up 67% of defense-centric suppliers but only 55% of category-management suppliers, a 12 percentage-point difference:

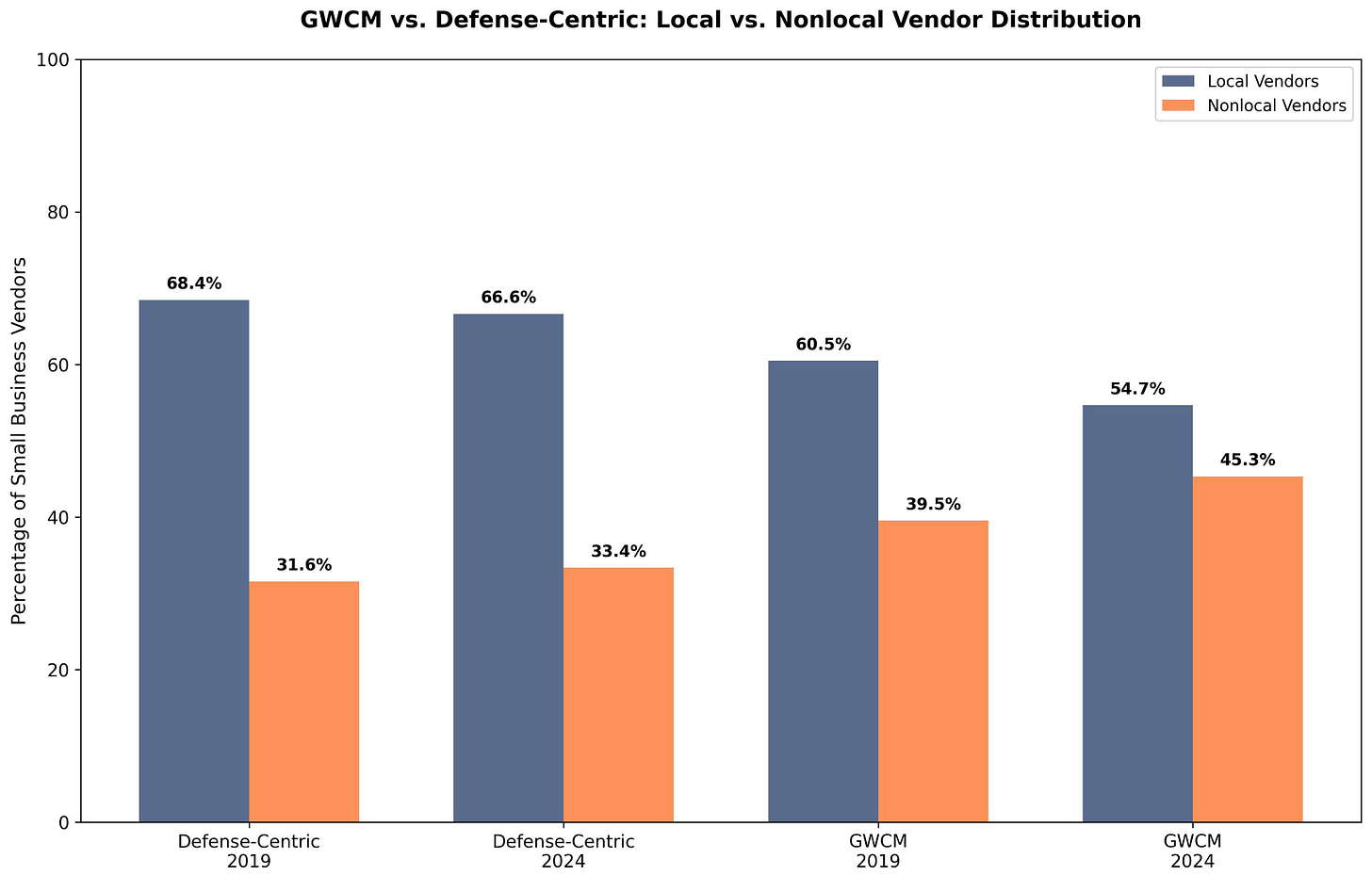

The adoption of category management accelerated the move away from local. OMB’s original memo in 2019 had allowed agencies to treat some local contracts as category-managed, but that was primarily a bookkeeping exercise. The new memo pushes agencies to use so-called Best-in-Class contracts, which are national in scope. That will make matters even worse for local businesses.

From 2019 to 2024, the percentage of local vendors in the category-management sectors dropped 5 percentage points, from 60% to 55%. Meanwhile, the drop outside of category management (in the defense-centric industries) was imperceptible:

It’s striking that local small businesses started out the era with over 60% of the vendor share, even within the category-management sectors. As former OSDBU director Desmond Brown (OPM and VA) always says government contracting is a relationship business. The prevalence of local firms proves that out. It’s a lot easier to capitalize on your relationships when the government is mostly buying from local businesses that the buyer might know personally.

That is changing. In 9 of the 10 industry sectors covered by category management, the share of national and regional businesses (which these graphs refer to as “nonlocal”) increased between 2019 and 2024. Professional services and transportation shifted the most away from local firms. Two sectors, human capital and IT, now have nonlocal shares of over 60%:

An economy-wide trend

The shift away from local isn’t limited to government contracting. The whole American economy is becoming more national, especially in services. In my area, I see that particularly among veterinarians. But you can see the signs everywhere: the mom-and-pop shop closing up because of competition from Wal-Mart and Amazon. Or the neighborhood garage converting to a Meineke. In contracting, though, the difference has always been that the procurement system was accountable to Congressional politicians focused on their local constituencies, particularly small-business owners. In fact, the whole concept of small-business preferences traces back to then-Senator Truman's 1941 speech decrying how military purchasing was becoming geographically centralized.

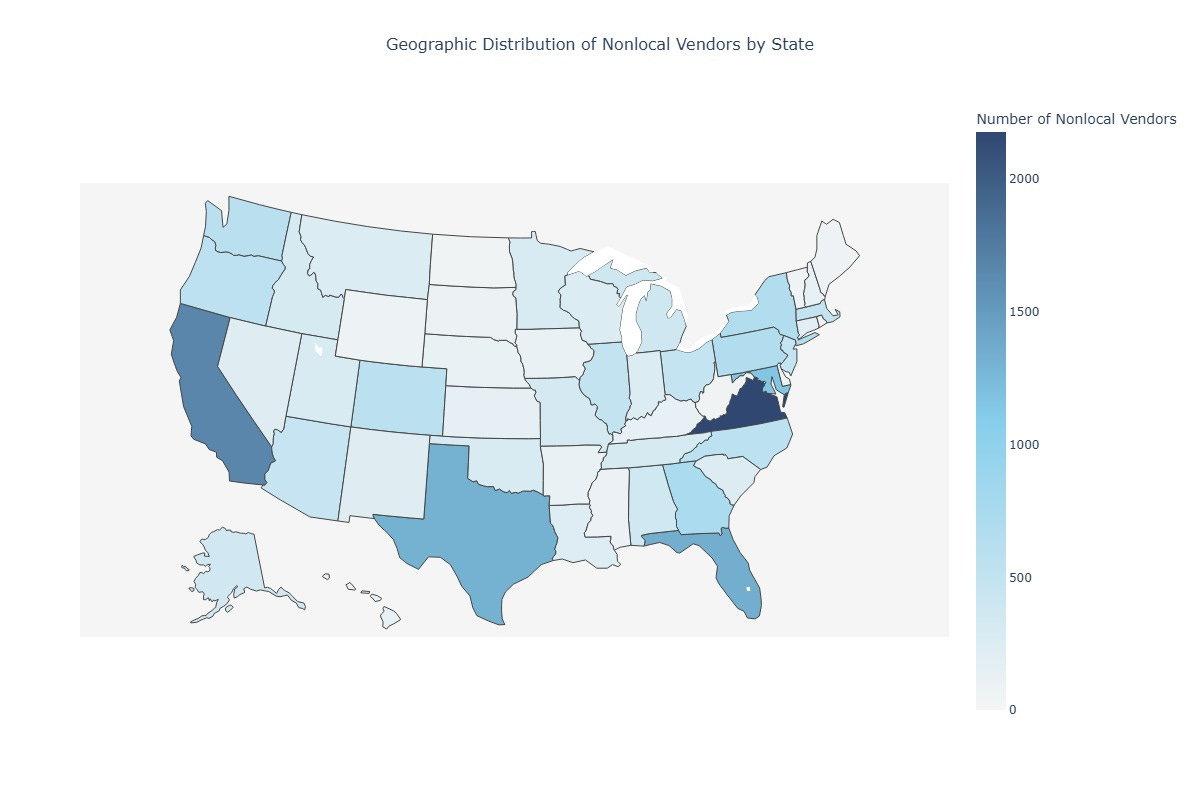

Back in the 1940s, the centers of Federal contracting activity were New York and Detroit. Today, it’s Virginia, Texas, and Florida. This map shows the states with the most nonlocal small-business contractors—that is, the ones that work on projects outside of their state. The top five states for these national and regional firms are Virginia, California, Florida, Texas, and Maryland:

How contractors will respond

OMB’s new guidance accelerates the shift away from local small businesses. Contracts will get larger, and the purchasing will be centralized at GSA rather than performed by local buyers.

And, just as local firms responded to the retail-level consolidation, small businesses will respond to consolidation in contracting. Surviving firms will need to associate with geographically dispersed partners, merge or get acquired, or consider franchise-type arrangements. As lawmakers worried in the 1940s, this could slow economic activity in local communities that aren’t contracting hotbeds. Long-term, consolidation may lead to less competition, particularly where the Federal government is the major buyer.

From the government’s point of view, SBA may want to consider the level of industry consolidation within contracting for its small-business size standards. Regardless, we will undoubtedly see the number of small-business participants continue to fall. The remaining question is whether policymakers will pull back on their efficiency focus as the local small contractors disappear.

Sam Le is a Virginia- and D.C.-licensed attorney. His website is www.samlelaw.com.

I corrected an error above: The title of the OMB memo is Consolidating Federal Procurement Activities, not Correcting Federal Procurement Activities.

This data with the new processes and facts around it gives GovCon a complete picture of how small businesses might (will) be impacted under consolidated buying. Great analysis and info for small businesses, and also large businesses seeking subcontractors and suppliers to meet their subcontracting goals. This is exactly the information folks need to help strategize next steps in this new buying era.