ATI Government Solutions and SBA's Limitations on Subcontracting

The law that applies to the SBA suspension includes several nuances and a big exception

I’m going to assume that readers have heard of or even seen the YouTube video that led to SBA suspending ATI Government Solutions from government contracting last week. My big admission for the rest of this article is that I have not watched the video.1

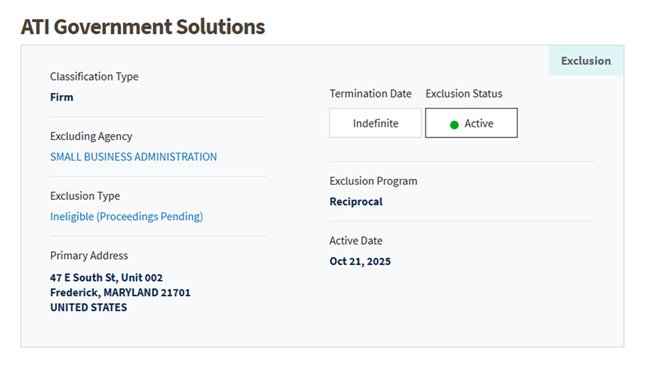

That said, I know the high points. ATI Government Solutions is an 8(a) participant owned by the Susanville Indian Rancheria. As an entity-owned 8(a) firm, ATI ordinarily would be eligible for enhanced 8(a) benefits, including sole-source awards from the Department of Defense up to $100 million. But SAM.gov now shows that ATI Government Solutions and three associated individuals have been suspended by SBA. The suspension—which is governed by Part 9.4 of the FAR—continues indefinitely, pending suspension-and-debarment proceedings by SBA. It means that ATI cannot receive new awards. Unless an exception applies, ATI is also ineligible to receive options, task orders, or most subcontracts.

The coverage speculates that ATI acted as a “pass-through,” meaning it won contracts as a tribal 8(a) firm but then passed on the work to other companies to perform the contracts. There is a rule against 8(a) pass-throughs. But that rule—the limitations on subcontracting—has important exceptions where a pass-through would be compliant.

To show that ATI broke the law, the Federal government would need to show a violation of the limitations-on-subcontracting rule for a specific contract. It’s not enough to say that ATI has a policy of inviting pass-throughs. Talking about pass-throughs is not illegal. The limitations-on-subcontracting rule operates on a contract-by-contract basis, and it operates differently depending on the contract.

The law on limitations on subcontracting

For services contracts, the Small Business Act requires that the awardee of an 8(a) contract not spend more than 50% of the contract with subcontractors:

in the case of a contract for services, [the 8(a) contractor] may not expend on subcontractors more than 50 percent of the amount paid to the concern under the contract

On some contracts, however, passing through as much as 85% of the contract is perfectly legal. It depends on the industry. That’s because, when Congress wrote the law on pass-throughs, Congress set a specific limit of 50% on subcontracting for services contracts and supplies contracts. But the Congressional legislation allows SBA to set a different limit for other types of contracts. SBA has done exactly that for construction contracts: The limit on subcontracting for general construction projects is 85% and for specialty trade contractors is 75%.

SBA actually has the authority to raise the limit for services and supply contracts too, but SBA has never done that. The agency has just defaulted to the Congressional limit of 50%.

It’s also important to understand that the subcontracting limit is a legal requirement that applies only to set-asides. Contracts with large businesses don’t have a limit on subcontracting. Large businesses—and even small businesses that win full and open contracts—can subcontract without any limit. Similar to the nonmanufacturer rule, which I wrote about previously, the limitations on subcontracting apply only to a small business on a set-aside contract.

It looks like ATI primarily works on services contracts, based on a quick review of USASpending.gov. ATI’s services contracts would be subject to the 50% limit on subcontracting, if awarded through the 8(a) program.

One issue that is becoming more common is how the subcontracting limits apply when the award is a task order. As more Federal purchasing moves to ordering vehicles—where the contract is just a license to seek future task orders—it is possible for a small-business contractor to fall below the subcontracting limit on individual task orders, provided it complies across the whole 8(a) ordering contract. An agency has discretion to apply the limit to an individual order, but that means the agency is not required to do that. If agencies don’t apply the order-level limit, that means an 8(a) firm could subcontract 80% on one task order off an 8(a) contract, provided the firm self-performs 80% on a similarly valued task order off the same contract. The self-performance cancels out the subcontracting so that the firm gets to 50% across the whole contract.

In December 2024, SBA revised its rules on how the subcontracting limits apply where multiple agencies can order off the same set-aside vehicle, such as in the case of a GWAC or OASIS+. The new SBA rule says that, in those cases, the ordering agency is required to apply the subcontracting limit to each order—it’s not just discretionary. But the rule is less than a year old and hasn’t been incorporated into the FAR (and might never be, given the FAR Overhaul).

It’s also notable that, at least for 8(a) contracts, the FAR and the FAR Overhaul use a different rule than the Small Business Act language quoted above. The Small Business Act and SBA rule focus on the flow of money; the contractor can’t spend with subcontractors more than 50% of what it receives from the government. The FAR has a different focus: personnel. The FAR requires that the 8(a) contractor perform at least 50% of the cost incurred for personnel. That’s language leftover from a prior version of the Small Business Act, but the FAR didn’t change it in the FAR Overhaul. What version wins out? It depends on what agency is doing the investigation and whether the contract includes more specific instructions or clause. With ATI, since SBA is handling the suspension, SBA is likely going to follow its own rule, which is the one about not paying more than 50% of the amount paid.

The exception for similarly situated subcontractors

Another way that the 8(a) contractor can exceed the limitations on subcontracting and still be compliant is by using the rule’s most common exception: the similarly situated subcontractor exception. That exception allows the 8(a) contractor to subcontract to another 8(a) contractor without the subcontract counting toward the limit. The exception basically encourages teaming by allowing multiple firms with the same designation can team together to win a contract.

The similarly situated exception has an interesting application for tribal-owned 8(a) firms, like ATI. On an 8(a) contract, the exception requires that the subcontractor also be an 8(a) firm, but it doesn’t require that the subcontractor be tribally owned. Since tribally-owned firms have the higher sole-source authority, a tribally-owned firm could win a large 8(a) sole-source contract and then subcontract most or all of the contract to an individually-owned 8(a) firm that would not be able to win the contract on its own.

An example of the similarly situated exception came up at GAO in 2021 in a case called Blueprint Consulting Services. The protester argued that the awardee of a set-aside GSA Schedule order, Appddiction, would violate the limitations on subcontracting because it would only perform 40% of a FEMA contract for IT modernization. But FEMA responded that one of the subcontractors that would perform about 30% of the award was a small business. That made the subcontractor eligible for the similarly situated exception. GAO agreed with the agency, ruling that Appddiction’s proposal didn’t show that the firm would violate the limitations on subcontracting.

Why the ostensible subcontractor rule isn’t a problem

In the past, even if an 8(a) contractor met the limitations on subcontracting, it still might have run afoul of the ostensible-subcontractor rule. The ostensible subcontractor rule comes from SBA’s affiliation rule, 13 CFR 121.103. Under the affiliation rule, SBA deems a small business to be affiliated with its subcontractor, where the subcontractor performs the primary and vital requirements of the contract. Essentially, SBA considers that subcontractor to be performing as prime along with the actual awardee; that’s why the subcontractor is ostensibly a subcontractor, giving the rule its name.

SBA used to receive lots of ostensible-subcontractor protests, and they were very difficult to adjudicate. Every contract is different, and every proposal for each contract is different. So SBA spent a lot of time determining, first, what the primary and vital requirements of the contracts were, and then combing through the proposals and protest submissions to figure out which company was performing those requirements. Even then, with such a fact-specific analysis, it could be a close call, so the protest decisions could be reversed on appeal.

But, after an amendment in 2023, the regulation now includes a major exception that, in many cases, swallows the whole rule. If the small business can show that it will satisfy the limitations on subcontracting, SBA will not find affiliation. This is such a big exception that recent cases are just as likely to apply the exception as the rule itself.

The Winergy case from SBA’s Office of Hearings and Appeals demonstrates how the exception works. Winergy accused AFIC of violating the ostensible-subcontractor rule on a VA contract for certifying the safety of research labs. Winergy had actually been successful in previous protests against AFIC using the same rule on similar contracts. And AFIC itself acknowledged that its subcontractor would do a substantial portion of the certification tasks. AFIC would perform contract administration, recordkeeping, documentation, compliance, and reporting.

Under the primary-and-vital standard, Winergy might have won its case. But OHA ruled for AFIC because, regardless of what tasks it would perform, AFIC demonstrated through a sworn declaration that it would meet the limitations on subcontracting. This was enough to overcome “any claim” of having an ostensible subcontractor, the OHA judge wrote.

These are the important questions to consider in any limitations-on-subcontracting case: Is the award at issue a contract or order? How much was actually paid to the subcontractor and what was the value of the contract? What is the size and status of the subcontractor? How ATI answers those questions may determine how long its suspension lasts and may have longer-term implications for the 8(a) program as a whole.

With 20 years of Federal legal experience, Sam Le counsels small businesses through government contracting matters, including bid protests, contract compliance, small business certifications, and procurement disputes. His website is www.samlelaw.com.

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice.

I have a long-time aversion to watching inauthenticity on screen—ever since I was a kid, I can’t stomach movies or shows with deception storylines. Memorably, that includes the scene in the 1982 Annie where Tim Curry—with a mustache as believable as James O’Keefe’s wig—and Bernadette Peters pretend to be Annie’s parents.

Excellent, easily understood presentation of the nuances, Sam. Thanks a million.