Small business contracting dropped in 2025. Unless you were an 8(a).

Despite all the scrutiny, the 8(a) program surged last year—by how much depends on what number SBA picks to publish

Amid the “full-scale” audit of their program, there’s a bright spot for 8(a) contractors. The Federal government set a new record for spending in the 8(a) program in 2025, according to the latest SAM.gov data. In fact, SAM.gov currently reports that 8(a) spending was up 80%. But I’ll explain later on why the real increase was far less.

All other small-business contractors have reasons to worry, though. Spending with small businesses outside the 8(a) program went down. It was the first such decrease in a decade.

And the government likely missed the women-owned, HUBZone, and service-disabled veteran-owned small business goals. The miss on the service-disabled veteran-owned goal is concerning. It will be the first time since 2011 that the Federal government has not met the goal for service-disabled veteran-owned small businesses.

All this comes from SAM.gov data, the official repository for Federal contracting data. (In 2026, SAM.gov is going to replace FPDS, which is where I have always gotten my data.) SAM.gov now includes all transactions from fiscal year 2025 after a 90-day delay. The SBA won’t publish the final data for several months, however. And there are good reasons for that. Agencies are still revising and updating their FY25 numbers. As we’ll see, that’s the difference between a $1.5 billion increase to the 8(a) program and a massive $20 billion increase.

8(a): speed over policy

Since inauguration, the 8(a) program has been in the cross-hairs. First, SBA announced that it was lowering the goal for small disadvantaged businesses from 15% to 5%. The SBA’s press release suggested that the agency believed that the goal was for the 8(a) program specifically. It’s not. But regardless, the lowered goal has the rhetorical effect of showing SBA’s shift away from supporting the program against attacks.

And then came the audits and investigations. First, SBA announced the full-scale audit. Then YouTube personality James O’Keefe found 8(a) contractor personnel willing to talk about pass-through contracts that may or may not be illegal. So the Department of the Treasury and then SBA itself went further with the audit. Now all active 8(a) firms have to respond to SBA by January 19th—a Federal holiday—with 13 sets of documents.

The 8(a) program was historically the SBA’s program for minority-owned businesses. It still reads as the program for Minority Small Business and Capital Ownership Development in the legal text of section 8(a). So there are lawsuits from conservative interest groups. One is seeking Supreme Court review. Another is still pending in Tennessee, and a third was recently filed in Louisiana. To me, the lawsuits don’t make much sense. The program no longer has any preferences for minority-owned businesses. The Louisiana case doesn’t even involve a Federal contractor; it challenges a small program run by Tulane University for Tulane alums. But the target is the 8(a) program.

The same reason that the 8(a) program is accused of being susceptible to fraud is why it remains as strong as ever. The program is fast. Unlike all the other SBA programs, the 8(a) program has an expedited sole-source award feature. Most 8(a) firms can receive sole-source awards up to $5.5 million. Firms owned by Alaska Native Corporations, Indian tribes, and Native Hawaiian Organizations have higher thresholds—up to $100 million in most cases.

In this contracting environment, the speed of the 8(a) program is its saving grace. The Federal government has a lot of money to spend at the end of the fiscal year. In 2025, it had more than usual because of DOGE-related contract terminations, a late Congressional budget, and fewer contracting officers on staff. That made all the difference for 8(a) firms. Agencies spent more money with the 8(a) program in the fourth quarter of FY25 than in any other three-month period in the program’s history. That led to the best year ever for the program.

The current SAM.gov data shows an unbelievable 80% increase in 8(a) contracting in 2025. That’s $20 billion more than 2024.

But it really isn’t to be believed. Just last week, a single agency—the State Department—reversed $19 billion of its 8(a) contracts from 2025. The reversal might be because of the latest actions from SBA and the Senate Small Business Committee. Or it might just be a strange accounting issue. (More specifically, it looks like State might have incorrectly entered an IDIQ maximum as an obligation, and then it fixed the mistake.) I’m not certain whether SBA will report the final figures with the $20 billion increase or not. Without the State Department’s reversed contracts, the increase was only $1.5 billion, just 1%. Either way, with a record-breaking year amid all the hubbub, the 8(a) program remains the big story in government contracting.

2025 wasn’t so good for everyone else

The 2025 data doesn’t show many bright spots outside of 8(a). Women-owned contracting was way down. That program will probably have its lowest percentage in a decade, well short of the 5% goal.

HUBZone will almost certainly miss its 3% goal again. And, if you don’t count the State Department’s reversed contracts, the HUBZone program will break a nine-year streak of year-over-year increases.

The worst result comes from the service-disabled veteran-owned small business program. SDVOSB contracts dropped to 4.7% in the current data, over $2 billion short of the 5% goal. Agencies will miss the governmentwide SDVOSB goal for the first time since 2011. The goal was raised to 5% in 2024, and agencies met that handily last year. There was even some talk about raising the goal even further. But now, agencies can’t even get to the existing goal. So I don’t know how raising the goal would do any good.

SDVOSBs got less money where it counts the most. The top three agencies for SDVOSBs—VA, Defense, and DHS—all spent less with that category percentagewise.

So 8(a) spending was up, and SDVOSB’s was down. SBA would like the story to be the reverse. SBA’s Veteran Day press release was about pulling resources from the 8(a) program over to SDVOSB certification. But this is another case of circumstances overcoming policy. The decrease in SDVOSB contracting results from the government’s shift away from value-added resellers and toward OEMs. The biggest NAICS industry by far for SDVOSBs is 541519—the code that covers value-added resellers. (By contrast, in the 8(a) program, the biggest industry is construction). So if the government is going to spend less with resellers, that means spending less with service-disabled veteran-owned firms.

As for small businesses in general, the long-running trend of less accessibility continued. In my preliminary figures, the number of small businesses participating in prime contracting dropped 8% to 56,000. New entrant small businesses fell to 8,200, the lowest figure since 1989. I wrote about why contracting is becoming less accessible, and why the FAR Overhaul makes the situation worse in a piece a few months ago:

If I were to pick one type of contractor that I would have wanted to be in 2025, it would be a Native-owned 8(a). They were the best-off group in the best-off program. Native-owned 8(a) firms—comprised of firms owned by Alaska Native Corporations, Indian Tribes, and Native Hawaiian Organizations—won 65% of 8(a) dollars in 2025. That’s up slightly from 2024’s figure of 63%, and the largest proportion to Native-owned firms in the program’s history. Just 10 years ago, Native-owned firms received $6 billion in 8(a) contracts. Now, at $17 billion, it’s almost triple that.

This shows the government wants to buy faster

The story behind the story for 2025 was speed. Faster contracting is why the FAR Overhaul took a hatchet to Part 13 and elevated Part 12. It’s why DoD is shifting to commercial buying. And it’s why the 8(a) program had its best year yet.

Last year was supposed to be the year of consolidation. The biggest policy emphasis from the FAR Overhaul was consolidating contracting, both to GSA and with best-in-class vehicles. But the data shows a tension between speed and consolidation.

Consolidation took a backseat. The GSA Schedule had its first decline ever, according to the SSQ+ dataset that begins in 1997. As fast as the Schedule might be, it isn’t as fast as 8(a) sole sourcing.

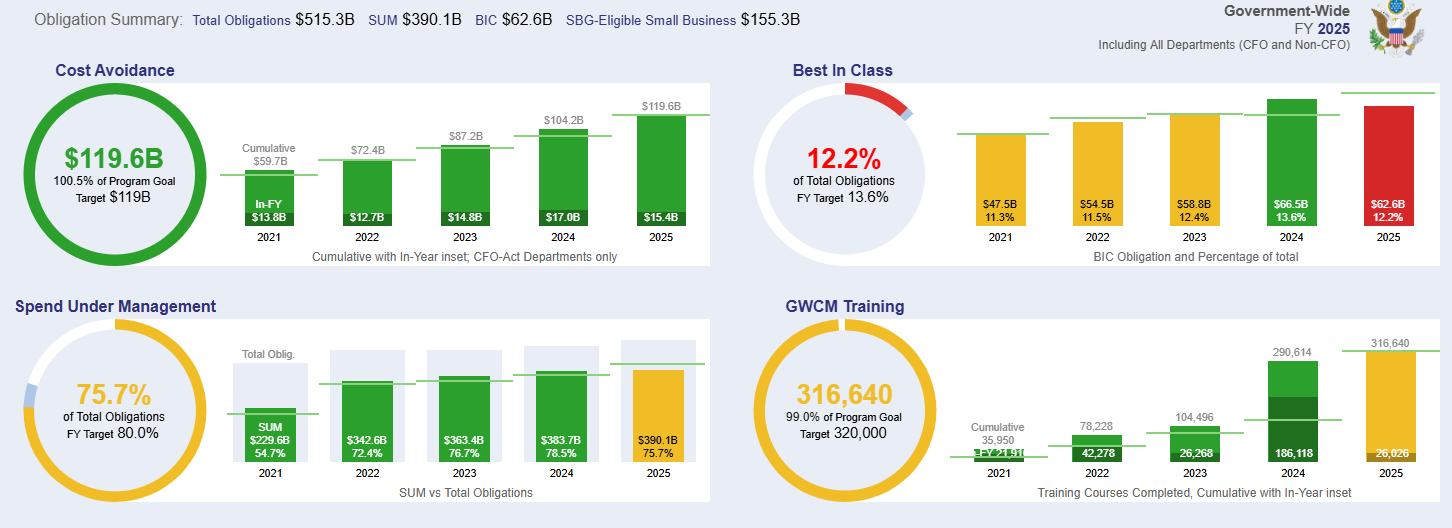

Prior to this year, the Category Management program had been slowly making inroads. For a brief period, the highest level of managed contracts—the so-called Best-in-Class contracts—was going to be mandatory for agency use. The FAR Overhaul drafters reversed that decision. But they still emphasized that best-in-class was “prioritized.”

Agencies didn’t get that message. The use of best-in-class contracts fell to its lowest level since 2022, and the government fell well short of its 13.6% best-in-class goal. With an even higher level of Category Management on the horizon—the forthcoming “required use” designation—it’s not certain that best-in-class will survive the next few years.

To me, the data shows that—despite policy uncertainty—things aren’t as different as you might expect. The FAR Overhaul might have cut 20% of regulatory text, but, so far, it hasn’t actually revolutionized much. SBA took aim at the 8(a) program. But the program has withstood the challenge so far. And Best-in-Class has not taken over the world. If anything, agencies are actually moving away from consolidation.

The takeaway from all this is that speed matters most—more than consolidation and more than new FAR Overhaul policies. My experience is that small businesses in the SBA programs are the best at mobilizing and executing quickly. That will be their best selling point for 2026 and beyond.

With 20 years of Federal legal experience, Sam Le counsels small businesses through government contracting matters, including bid protests, contract compliance, small business certifications, and procurement disputes. His website is www.samlelaw.com.

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice.