The fraud that could bring down the 8(a) program wasn't for millions. It was $22,000.

SBA is auditing every 8(a) firm, but it's not because of hundreds of millions in fraudulent contracts

Participants in SBA’s 8(a) program now have less than three weeks to respond to SBA’s sweeping audit letter. The letter accuses the 8(a) program of being “a vehicle for institutionalized abuse at taxpayer expense.” As a result, the 4,300 participants must submit 13 categories of financial documents by January 5. One of the documents—a “sub-ledger schedule”—isn’t even a typical accounting report. Most of the Google hits for the term “sub-ledger schedule” point back to SBA’s letter. (One of the unexpected benefits of running a law office is that I’ve become really familiar with small-business accounting.)

Meanwhile, on Capitol Hill, the Senate Small Business Committee held a 90-minute hearing about fraud in SBA programs. The Chair introduced a “Stop 8(a) Contracting Fraud” bill to suspend the program while SBA conducts the audit. The primary witness, Luke Rosiak, called for ending all set-aside programs—not just the 8(a) program—because they are “vulnerable to corruption.” Another witness went even further. John Hart of Open the Books said the U.S. Small Business Administration shouldn’t even exist. We should “return business to business,” Hart testified. Committee Chair Joni Ernst replied, “That is pretty profound.”

It’s now a very real possibility that Federal agencies may reduce or even stop the use of the 8(a) program, based on this aura of fraud and corruption. Ernst wrote letters to 22 agency heads requesting that they pause all 8(a) sole-source contracting. SBA already has the playbook for slowing the program to a trickle: It can pull the 8(a) partnership agreement, as it did for USAID earlier in the year.

You would think, then, that this massive audit, Congressional inquiry, and talk of corruption are premised on hundreds of millions, or even billions, of dollars in fraudulent in 8(a) contracts. They’re not. There’s one contract. It was worth $22,000.

The $22,000 sole-source contract at the center of the scandal

But what about the “$550 million” in fraud that SBA Administrator Kelly Loeffler cited in ordering a “full-scale audit” of the 8(a) program? Go back and read the DOJ’s June press release closely: The $550 million figure refers to government contracts, not 8(a) contracts.

The company at issue in the fraud, Apprio Inc., reportedly bribed a USAID contracting officer to win the contracts. The bribes included cash, laptops, and NBA tickets, totaling $1 million in value. In exchange, the USAID contracting officer, Roderick Watson, reportedly funneled sole-source 8(a) contracts to Apprio. Watson pleaded guilty and is awaiting sentencing.

When Apprio graduated from the 8(a) program in 2015, the scheme allegedly shifted to using another 8(a) firm, Vistant. Vistant would then subcontract to Apprio.

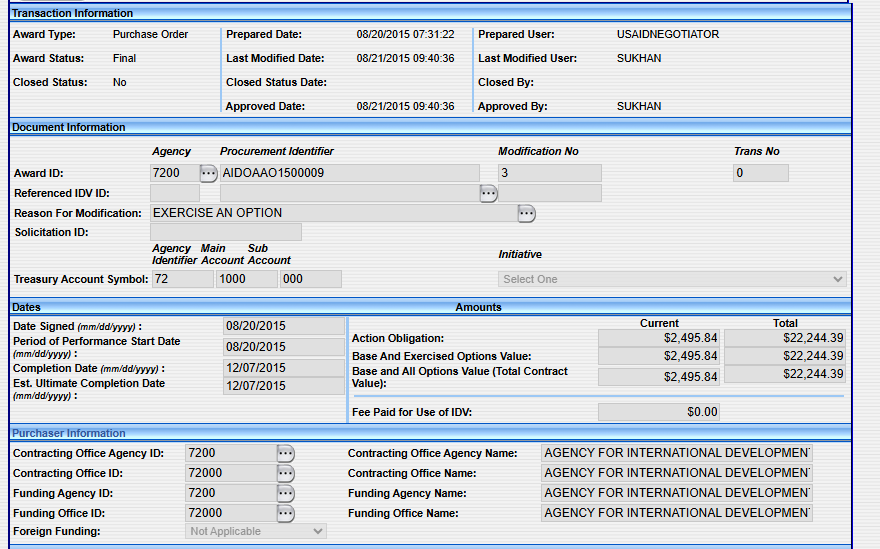

Apprio has received $262 million in Federal contracts, and Vistant has received $221 million. So that’s within the range of that $550 million figure. But very little of that was from 8(a) contracts. An even smaller amount was on 8(a) sole-source contracts from USAID, where Watson worked. Of the $262 million to Apprio, only $22,244 was awarded by USAID to Apprio using the 8(a) program. That all came through a single contract:

That $22,000 contract to Apprio was for a website to be used by USAID lawyers. Apprio would “create a fully-functional internal intranet website accessible to USAID’s attorneys in USAID’s Office of the General Counsel.” I remember trying to procure a similar website when I was an attorney with SBA’s Office of General Counsel. The price does not sound outrageous. If USAID had bought monthly Clio subscriptions for 100 lawyers instead, that would cost roughly $10,000 per month. And the Apprio contract was probably for a perpetual license.

Even if USAID lawyers didn’t get the website at the end of the $22,000 contract, it’s not a huge amount of money. It’s about the cost of a new Toyota Corolla.

All the other contracts to Apprio—the company at the center of the scheme—were with other agencies or outside of the 8(a) program. Based on its settlement—Apprio paid $500,000—Apprio was a bad apple. But it couldn’t have used the 8(a) program for “institutionalized abuse.” The USAID 8(a) contracts were less than 0.01% of its contracts.

Vistant paid $100,000 to settle its allegations. Vistant has more 8(a) contracts at USAID to its name: four altogether. But three of those were competitive 8(a) contracts. The DOJ allegation was that Watson, the USAID contracting officer, was able to steer contracts to Apprio “without a competitive bid process.” So the competitive contracts aren’t the fraud. It’s questionable that bribing a contracting officer would help a company win a competitive award. As most people in contracting know, an agency’s contracting officer usually awards to the company selected by an evaluation panel of program officials.

That leaves one remaining USAID contract to Vistant. That contract, a $13 million award from June 2020, was coded by USAID as an 8(a) sole-source contract. But I’m not sure that it was actually an 8(a) contract.

For individual-owned 8(a) firms like Vistant, 8(a) sole-source awards are capped at (back then) $7.5 million.1 The only way that Vistant could have received a $13 million sole-source award—almost double that threshold—was to be a Native-owned firm (it’s not), or for USAID and SBA to jointly determine that Vistant was the only 8(a) contractor available to do the work. That determination is extremely rare. Of the 9,000 sole-source contracts to individual-owned 8(a) firms in fiscal year 2020, the contract to Vistant was the only one across all Federal agencies that exceeded $7.5 million at award. That’s right: Vistant’s was one out of 9,000. So it was an exceptionally strange contract, a data-entry error, or—just as likely—a strange consequence of that weird early COVID period.

And, even if the unusual $13 million sole-source contract was fraudulent, it wasn’t because of the Biden Administration. In 2021, the Biden Administration started raising the contracting goal for small disadvantaged businesses, first to 11% and then eventually to 15%. Ernst suggested that Biden’s goal increase led to “exploitation by wrongdoers.” But Vistant’s $13 million sole-source contract was awarded by USAID in June 2020, at the tail end of the first Trump Administration.

So I’m skeptical that Vistant’s was actually an 8(a) contract. But maybe it was. If Congress wants to address fraud of this sort, it should ban sole-source contracts to individual-owned firms above the sole-source threshold. That process is in section 8(a)(1)(D)(i)(I) of the Small Business Act. The repeal would have virtually no impact on how the program operates. I found only 39 awards—out of 215,000—that met the same criteria: 8(a) sole source to an individual-owned firm above $7.5 million at award. It’s not a common thing.

Let’s assume that the $22,000 contract and the $13 million contract were both fraudulent 8(a) contracts.2 That doesn’t make the 8(a) program a “fraud magnet.” The total amount of the Apprio fraud was $550 million. The 8(a) sole-source portion of that was $13.022 million, or just 2%. Since the 8(a) program is 4% of government spending, proportionately fewer 8(a) contracts were a part of the bribery scheme. For more about why the 8(a) program is actually less susceptible to fraud, see Holly Mathnerd’s excellent deep-dive:

If the numbers don’t show widespread fraud, why is this scandal threatening to end the 8(a) program?

Why ATI Solutions might be compliant

The immediate answer is that the James O’Keefe video also suggests 8(a) fraud. In the video, an employee of ATI Government Solutions states the company does “about 20%” of the work on 8(a) contracts. SBA recently stated in a press release that the video represents “mounting evidence” that the 8(a) program is “a pass-through vehicle for rampant abuse and fraud.”

Yes, if true, 80% of pass-through works seems like a lot. But it’s not necessarily fraud. It struck me, when reading initial reports about the video, that the figure the employee cited was oddly precise. That number, 20%, represents the minimum amount that a small business can do legally through a mentor-protégé joint venture. SBA rules allow the joint venture as a whole to do as little as 50% of the work of a services contract. Then the small business can do as little as 40% of the work of the joint venture. You can stack those minimums, so the minimum legal amount of self-performance is 40% times 50%, which equals 20%.

ATI Government Solutions could also have complied with the rules against pass-throughs by using the “similarly situated entity” rule. That allows an 8(a) firm to subcontract to other 8(a) firms without the work counting against the maximum subcontract limit. These subcontracts are quite common. And that’s even more the case with a Native-owned firm like ATI. Individual-owned 8(a) firms can’t access high-dollar sole-source contracts, so they can team with Native-owned firms to perform larger sole-source opportunities. That is all legal too.

I’d be surprised if a sophisticated contractor like ATI wasn’t doing one of those things: mentor-protégé and subcontracting to other 8(a) firms. That doesn’t mean that ATI wasn’t also doing something wrong. But the 20% number by itself does not categorically equate to fraud. Maybe it is shocking to the conscience. In that case, though, the solution is to change the rules—raise the protégé’s required work or restrict the use of similarly situated entities. Don’t punish the company for abiding by the rules.

If 20% can be legal, there has to be something more. There could be a concerted scheme, as with Roderick Watson. The facts haven’t come out yet. But it already sounds like the Senate Committee and SBA have made up their minds.

The focus on Indian Americans

So what is this really about? The Senate hearing on Wednesday raised an intriguing possibility: The opponents of the 8(a) program don’t want Indian Americans in the program. I hadn’t remotely considered this, but the first witness went on and on about how “Indian Americans are the wealthiest demographic in America with a higher median income than whites.” He said, “Indians have never been underrepresented in the field of IT; they’re actually overrepresented in that field.”

Rosiak even named a specific 8(a) owner and the location of the owner’s house. Rosiak described the owner’s house. He showed a photo of the house. At an open Senate hearing!

The allegation from Rosiak was that “people from the country of India gobble up a lion’s share of 8(a) contracts.” That’s not true, by the way. Black-owned firms receive more in 8(a) contract dollars than South-Asian-owned firms ($2.6 billion vs. $2.3 billion in 2024). And they both receive far less than firms owned by Alaska Native Corporations, Indian Tribes, and Native Hawaiian Organizations. Together, those three categories receive over 60% of 8(a) dollars.

And, even if Indian-American-owned businesses were receiving a disproportionate share of 8(a) dollars, one owner’s large house isn’t fraud. In fact, the 8(a) program encourages this. By law, all 8(a) owners must be “economically disadvantaged.” This means their calculated net worth and total assets must be less than legal thresholds. But, in the 8(a) statute, Congress forbade SBA from including the value of the owner’s primary personal residence in the calculation. This encourages successful 8(a) owners to pump earnings into their homes. Other successful business owners might buy art, fund college savings, or invest in rental properties. Owners of 8(a) firms that do that risk their economically disadvantaged status. So they buy bigger houses and renovate them. There’s nothing fraudulent about a small-business owner having a big house. Remember the Chris Rock joke?

This isn’t the only recent issue involving Indian Americans to be politicized. The New York Times recently reported on Nalin Haley, Nikki Haley’s son, calling for a complete ban on H1-B visas. Between two-thirds and three-quarters of H1-B visas go to workers from India. Nikki Haley’s parents immigrated from India. But 8(a) participation can’t be based on visas. By law, all 8(a) owners must be U.S. citizens. That includes the owner named in Rosiak’s testimony.

The bigger point about Rosiak’s testimony is that it revives the practice of putting 8(a) owners into racial groups. This is a form of, as Noah Smith called it, racial collectivism. SBA doesn’t do it anymore. After the Supreme Court’s college-admissions ruling, SBA stopped automatically qualifying owners based on racial status. (SBA was following a directive from a lower court that found the practice unconstitutional.) Now, all current and future 8(a) owners have to submit a narrative. The narrative explains how the owner, as an individual, experienced discrimination. The narrative process—which the Department of Transportation recently adopted for the state-level DBE program—gets the Federal government away from treating people as members of groups. Instead, the narrative treats the owners as individuals. The business owner that Rosiak named had to submit a narrative, describing incidents of discrimination. SBA found the narrative compelling enough to allow his firm to continue in the 8(a) program, based on the owner’s individual circumstances.

Maybe in the future, admission to the 8(a) program can be more closely tied to the program’s goals of business growth and community development. It seems strange to me that SBA—the government agency tasked with supporting small businesses—is deciding who has suffered discrimination and who hasn’t. So the narrative process isn’t perfect. It’s probably an interim solution while lawmakers decide on the future of the program.

That future is less bright today than it was a few months ago, with this ongoing audit and the Congressional letters. The audit is very likely to find something; as Dean Jessica Tillipman and I recently discussed, business owners might not fully understand how these complex rules work (though, in some cases, the rules can work in their favor, such as with the similarly situated-entity rule). The audit might find fraud. But, so far, the total amount of confirmed 8(a) fraud is barely enough to buy a Corolla.

With 20 years of Federal legal experience, Sam Le counsels small businesses through government contracting matters, including bid protests, contract compliance, small business certifications, and procurement disputes. Sam obtained his law degree from the University of Virginia and formerly served as SBA’s director of procurement policy. His website is www.samlelaw.com.

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice.

The cap is lower for services contracts—now $5.5 million. The Vistant contract at issue was a services contract, with the NAICS for Administrative Management and General Management Consulting Services.

Valuing the fraud at $13 million is an overstatement because it accounts for the full value of the initial award. The allegation is that Apprio steered subcontracts to itself through Vistant. The value of Apprio’s subcontract was only $1.4 million.

A well done and detailed analysis of not only the 8(a) program, but what appears to be the fate of all small business set-aside programs. Federal small business prime and subcontractors would do well to closely follow legislation going through the small business committees and congress. It appears the ultimate intent is to do away with all set-aside programs. This will have a significant impact the 25% small businesscontracting goal. So much for “Small Business is the backbone of the economy, providing jobs, driving innovation and contributing significantly to the GDP.” The mantra used by all presidential candidates. I hope I’m wrong!

Thanks for the analysis. 🧐