Why the FAR Overhaul's changes won't shrink the 8(a) program

Part two of a three-part series on the rewrite of FAR Part 19 on Small Business. Plus another change you might have missed.

We can now dispense with the fiction that the FAR Overhaul was just an exercise in reverting the FAR to its “statutory roots.” There were so many policy changes—all unrelated to statute—that I need three separate articles to cover the changes to FAR Part 19. That’s the part that was renamed from “Small Business Programs” to simply “Small Business,” which is itself a statement on the second-most-important policy change in Part 19: the shift away from the 8(a) program to the general small-business preferences. I covered the most important change—the preservation of the Rule of Two—in last week’s edition: The Rule of Two survived. But it’s still primed for legal and legislative battles.

The shift away from 8(a) doesn’t make the top spot because I don’t think it’ll make a difference to the program in the aggregate. The changes will be in who gets contracts and what type of contracts get awarded through 8(a). But this isn’t a death-knell for the program. In fact, if it weren’t for the slowdown in 8(a) application reviews, I’d say 8(a) firms don’t actually have much to worry about. There’s also the specter of possible additional changes to the social-disadvantage definition following the Department of Transportation's requirement for disadvantage narratives. A lot is happening with the 8(a) program, but the FAR Overhaul isn’t the most significant change.

The Overhaul drafters thought it was important, though. Larry Allen, the GSA associate administrator for government policy, revealed in an interview with Holland & Knight that SBA will issue conforming changes to that agency’s regulations to match what is in the FAR Overhaul. That tells me a lot. First of all, his statement answers the big question I had in my initial reactions to the 8(a)-related policy changes: How can the FAR Overhaul do this when SBA regulations say something different? According to Allen, the FAR Overhaul drafters have enough influence to actually change SBA regulations. So whatever the Overhaul says about SBA goes.

And second, Allen’s statement reveals a lot about the FAR Overhaul’s priorities. Basically, the Overhaul had carte blanche to make SBA regulatory changes. With all that power, the one thing they wanted to do was change the operation of the 8(a) program. Think about that: The Overhaul was fine with size protests, procurement-center-representative reviews, and subcontracting plans (which are alive and well, by the way)—all of which have the potential to slow down procurement timelines. The one thing the Overhaul picked was the 8(a) program. Clearly, the Overhaul drafters were trying to change the 8(a) program, possibly to make the program a smaller part of contracting.

What the FAR Overhaul changed in the 8(a) program

In short, the FAR Overhaul makes three changes to the 8(a) program, the first of which impacts all the socioeconomic programs:

Small business set-asides are now in parity (i.e., on a level playing field) with set-asides in the socioeconomic programs—8(a), HUBZone, service-disabled veteran-owned, and women-owned. Previously, the FAR stated that agencies “shall first consider” the socioeconomic programs before proceeding with a small business set-aside above the simplified acquisition threshold. (And SBA’s regulations still use similar language.)

The “once 8(a), always 8(a)” rule no longer applies when an agency decides to award the follow-on contract through the HUBZone, service-disabled veteran-owned, or women-owned programs. Previously, agencies would need to keep the follow-on contract in the 8(a) program, or request and receive a waiver of the rule from SBA.

The Overhaul creates a preference for competitive 8(a) orders, even under the $5.5-million sole-source threshold that previously required agencies to use sole-source contracts when using the 8(a) program. The only exceptions were where SBA granted waivers “on a limited basis.” Now the Overhaul states that contracting officers “must first try” a competitive order using a multiple-award contract that SBA has approved for 8(a) competition below the threshold. These contracts include 8(a) STARS, the 8(a) MAS Pool on the Federal Supply Schedule, and others as described in the ordering procedures for the contract.

These are big changes as far as policy goes. Every one of the old rules had been in place for as long as I can remember: the priority of socioeconomic set-asides, the once-8(a)-always-8(a) rule, and the sole-source requirement below the threshold. The 8(a) program began as sole-source only, so that change in particular deviates from the original design of the program.

If the FAR Overhaul drafters were trying to shrink the 8(a) program, these changes won’t do it.

First, the “shall first consider” language was never enforceable anyway. A recent GAO case demonstrates why. The agency switched a solicitation from a set-aside for service-disabled veteran-owned small businesses to a set-aside for all small businesses, regardless of socioeconomic status. An SDVOSB protested. The agency argued that there weren’t two SDVOSBs expected to submit offers, and the protester disputed that point. But GAO said the specific number of potential SDVOSB offerors didn’t matter because “shall first consider” doesn’t come close to meaning “require”:

While both the FAR and SBA regulations require agencies to consider setting aside a procurement for certain subcategories of small businesses before setting aside for all small businesses, neither the FAR nor SBA regulations ultimately require agencies to do so, even if an agency finds that there are two or more responsible firms from a certain subcategory likely to submit fair market offers.

Second, the “once 8(a), always 8(a)” rule probably kept a large number of contracts out of the program at the same time that it kept some in the program. Agencies know the rule, and it discourages them from using the program in the first place. They don’t want to be locked into using 8(a) firms forever. That’s especially true if the agency is using the program mostly to reach a specific contractor and that contractor won’t be in the 8(a) program—which is limited to nine years—when it’s time for a follow-on. I heard from many contracting officials that they wouldn’t consider the 8(a) program because of the “once 8(a), always 8(a)” rule. There’s no possible data to confirm this because SBA doesn’t track why agencies do or don’t use the 8(a) program. But my guess is that changing the rule will be close to a wash.

And, third, using competitive 8(a) orders will shift 8(a) awards from newer 8(a) firms to more established firms, particularly graduated 8(a) firms. Under SBA’s rules, you don’t have to be a current 8(a) firm to win a competitive 8(a) order. You need to have been 8(a) when you won the umbrella contract. But it’s possible that an 8(a) firm could win the contract in its ninth year in the program and get five additional years to compete for 8(a) orders. I wonder if SBA might rethink the policy that allows graduated firms to win orders if they begin to dominate 8(a) competitions, though.

So, to summarize, the FAR Overhaul of the 8(a) program removed a toothless rule, watered down a rule that kept about as many contracts out of the program as in it, and shifted 8(a) awards from newer firms to 8(a) graduates. Certainly, that changes the program. It becomes less about business development and more of a contracting method. But the program will continue at roughly the same volume—or at least if it doesn’t, it won’t be because of the FAR Overhaul.

What else might change the program: SBA’s application reviews and changes to the preponderance test

If the 8(a) program shrinks substantially, it’ll be because of something else. The most likely culprit is SBA’s continued slowdown in approving new 8(a) participants. The slowdown—from over 550 approvals last year to just 66 as of August—is a result of a number of factors: fewer staff, a new electronic application system, and the requirement for all individually owned applicants to submit a social-disadvantage narrative. There’s also an undercurrent of animosity toward the program for its perceived civil-rights roots, even though the program now has over 70% of its funds go to Native-owned or veteran-owned firms.

The new development from this week is the possibility that SBA might change the current preponderance test, which the agency applies to the social-disadvantage narrative. Last week, the Department of Transportation introduced its own requirement for a narrative in the DBE program. But DOT changed the standard for approving the narrative from what SBA uses by requiring that determinations of disadvantage be “not based in whole or in part on race or sex.” The new DOT rule, which went into effect on Friday, states:

To satisfy the [social and economic disadvantage] requirement and ensure all determinations of disadvantage are not based in whole or in part on race or sex, an owner must provide the certifier a Personal Narrative (PN) that establishes the existence of disadvantage by a preponderance of the evidence based on individualized proof regarding specific instances of economic hardship, systemic barriers, and denied opportunities that impeded the owner’s progress or success in education, employment, or business, including obtaining financing on terms available to similarly situated, nondisadvantaged persons.

That “in whole or in part” language continues a theme from the Justice Department’s July memo on unlawful DEI. That memo indicated that potential unlawful DEI includes the use of proxies that substitute for considering race. The memo listed “overcoming obstacle” narratives as one such proxy:

“Overcoming Obstacles” Narratives or “Diversity Statements”: A federally funded program requires applicants to describe obstacles they have overcome or submit a “diversity statement” in a manner that advantages those who discuss experiences intrinsically tied to protected characteristics, using the narrative as a proxy for advantaging that protected characteristic in providing benefits.

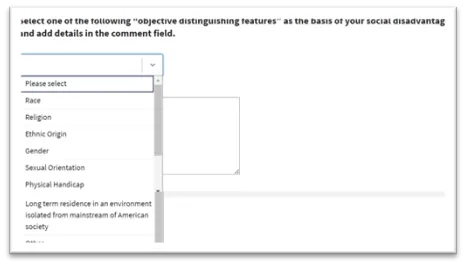

Applying that “in whole or in part” standard to SBA’s narrative review would dramatically change the process. Currently, SBA allows applicants to pick from a menu of “distinguishing features”—one that includes race and gender, as well as religion and physical handicap. The in-whole-or-in-part standard could take race and gender off the list.

And more to the point, barring the consideration of race and gender in any form, has two more important implications. One is that it would also prohibit any admission based on reverse discrimination. If a white-male-owned construction contractor in an area with very high DBE contracting levels could show that the contractor lost out on opportunities because of that, the in-whole-or-in-part standard would seem to block that showing.

The other is that the original impetus for all this change, the Supreme Court’s decision in the college-admission cases, explicitly allows for narratives to include race. Granted, I’m a government contracts lawyer, not a constitutional scholar. But even I can see that the Supreme Court’s decision would let someone use race as a distinguishing feature, provided the applicant’s individual attributes were downstream from their race. Chief Justice Roberts wrote for the majority, “nothing in this opinion should be construed as prohibiting universities from considering an applicant’s discussion of how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration, or otherwise.” And the majority provided a roadmap for using race that is far from the “in whole or in part” test:

A benefit to a student who overcame racial discrimination, for example, must be tied to that student’s courage and determination. Or a benefit to a student whose heritage or culture motivated him or her to assume a leadership role or attain a particular goal must be tied to that student’s unique ability to contribute to the university. In other words, the student must be treated based on his or her experiences as an individual—not on the basis of race.

I don’t understand how we went from that language in the Supreme Court’s opinion—which explicitly allows tying race to individual characteristics—to now saying that race can’t be considered even partially. And, as in the construction contractor example, the most harmed by that prohibition may be those who claim reverse discrimination, exactly the group that these changes were supposed to help.

Another Part 19 Overhaul change you might have missed

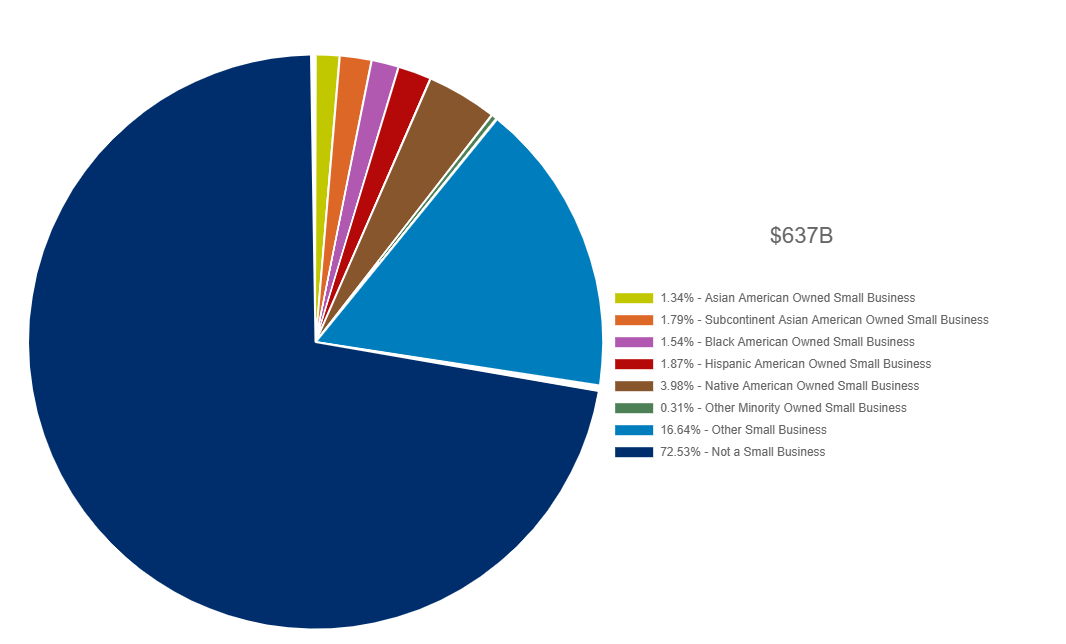

For the past four years, SBA has published so-called disaggregated data, showing the percentages of government contracts won by small-business owners based on race and ethnicity. I’m surprised each time I check and see that the data still lives on SBA’s website, as of this writing.

This disaggregated data relies on the fact that SAM.gov has a question that asks business owners to disclose their race or ethnicity. (Oddly, the question has a radio button, so you can’t pick more than one race.)

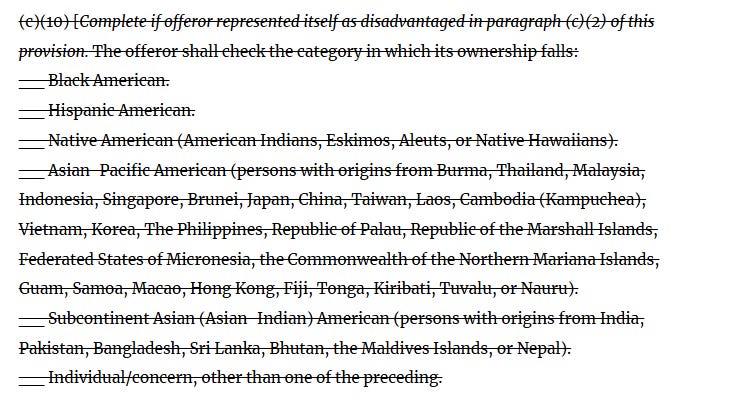

The FAR Overhaul deletes the race/ethnicity question:

It will be a while for the change to make it into SAM.gov, as the banner at the top of the site states. Implementation of the Overhaul won’t hit SAM.gov until at least January 2026. But once that happens, if SAM.gov deletes the question on the owner’s race, there will be no way to gather the disaggregated data.

With 20 years of Federal legal experience, Sam Le counsels small businesses through government contracting matters, including bid protests, contract compliance, small business certifications, and procurement disputes. His website is www.samlelaw.com.

PCRs slash timelines by ensuring early compliance (set-asides, anti-bundling) and streamlining acquisition strategy, preventing late-stage protests or regulatory rework that cause delays.